Deep in Richmond, Virginia, in the historic district of one of the country’s oldest towns, Ray Christian was born into hardship and poverty.

His parents couldn’t read, and there wasn’t much hope or potential in the run-down community.

“There are lots of towns around here that have populations like that, where people come down from the mountains into the closest big city,” he says. With few other options, he joined the Army at the tender age of 17, just two weeks after he had graduated from high school.

Christian served as a paratrooper in the infantry, where he grew up and saw the world over the course of his 20-year military career. Though coming up poor had given him a certain savvy, he was young and inexperienced and easily impressed. He had seen very little of the world, and was fascinated by the tales of guys who’d been to college or had families or fought overseas.

“When I joined the Army, I was surrounded by what I would call the best storytellers on earth,” he says. Christian didn’t have his own stories yet. That would come later.

At the age of 37, Christian found himself in the curious position of retiring before he had even hit middle age. He knew it was time to find another calling, so he went to college—then kept on piling up advanced degrees.

In the academic environment, especially graduate school, Christian found that his fellow students were unimpressed or even appalled by his military pedigree. “I came from an environment where any job you got with a uniform and a name on your chest was a good, respectable job,” he says. But now he was among young people who bragged about avoiding the service.

“I knew that I had to adapt,” he says. “It was like learning a different language, and being in a whole other culture. You have to be taken seriously.” While he was good at assimilating, the effort was alienating. He capped his education by becoming a Fulbright Specialist scholar, one of the most prestigious academic honors in the United States.

“I had to grow up in the ghetto, grow up in the Army, and grow up in academics, too,” Christian says. “For me, those three things never come together. People in each part of my life don’t really have relationships with other people in my life. I don’t usually find people in my tribe, as it were.” Making sense of these three disparate parts of his life has been the subject of his storytelling career, which was in some ways a natural extension of his PhD in education and oral history.

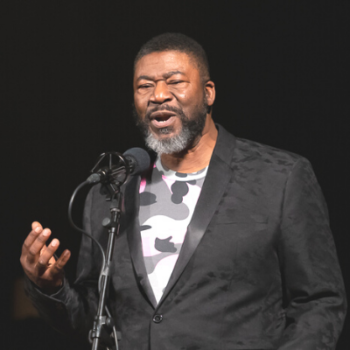

Christian, who now lives in Boone, North Carolina with an assortment of goats, chickens, and dogs, comes to the 2022 National Storytelling Festival as a New Voice. He was originally introduced to the stage in Jonesborough as the winner of the Festival’s Story Slam, and he was also a guest at Exchange Place.

In October, he plans to bring a selection of the stunning slice-of-life personal stories, which he considers a kind of history lesson.

“I’m always basically trying to teach Southern Black history without saying that,” says Christian. “I don’t talk about it explicitly, but everything that’s happened in the past has led us to where we’re at now.

“I try to make the history fun, and I’ve found that storytelling is the easiest way to do it,” he continues. “Donald Davis is giving you a lesson of what rural Appalachia was like, just in talking casually about his father. You’ve just been entertained, but you’re also learning.”

Christian will perform with 20 other featured storytellers at the National Storytelling Festival, October 7–9, 2022.